How countries could scale up their role in the voluntary carbon market: Brazil

intermediate

|

22 Oct 2024

Countries around the world have the chance to play a crucial role in scaling up carbon markets. Brazil, for example, is in a unique position thanks to its unparalleled natural capital and strong government support. It could serve as a supply hotbed and a centralized hub for global offset trading, setting the future pace of the market. A big investment opportunity in Brazil awaits, but players must develop the right frameworks now to ensure sustainable growth.

Key message

Brazil and other countries with abundant natural capital and strong government backing have the opportunity to play a key role in the voluntary carbon market. With major companies having set net zero targets, even the most aggressive abatement strategies will have residual emissions to be offset. Brazil could therefore be the model country for nature-driven climate mitigation.

Demand

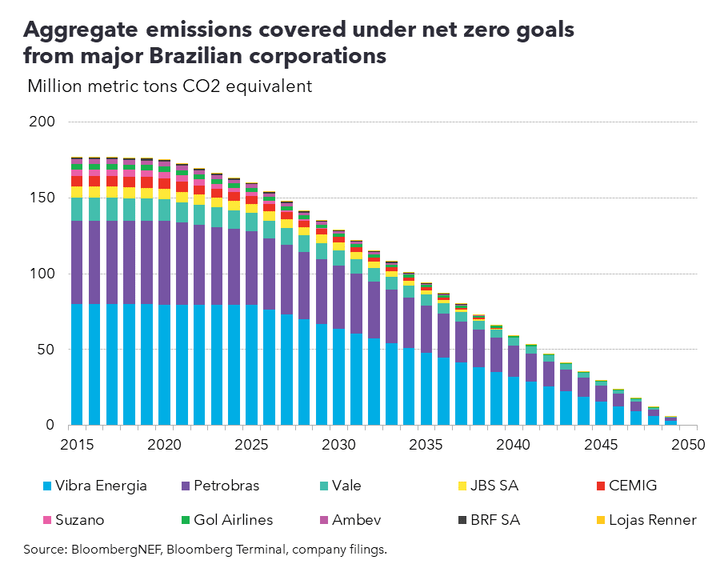

Most carbon offset demand today is driven by corporate emissions targets like those pledged by many major Brazilian companies. The 10 largest players in Brazil with net zero goals will collectively need to slash 177 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent (MtCO2e) from their annual emissions.

The impacts of these targets could be far larger as companies make them more ambitious. Both Petrobras and Vale only include Scope 1 and 2 emissions in their net zero goals, which come from their operations. The size of Vale’s net zero target would grow 55-fold if it were to include Scope 3 emissions from the use of its products downstream. The net zero target of Petrobras would multiply 10-fold with similar changes.

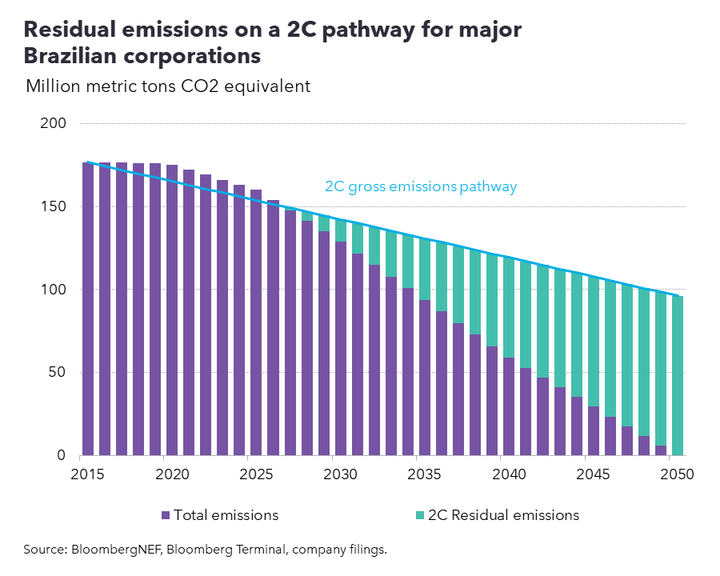

No company with a net zero goal will physically be able to reduce its emissions entirely over time, no matter how aggressive it is. It will reduce its gross emissions, or what it physically emits, as much as it can using mechanisms like clean energy procurement, fleet electrification, energy efficiency and augmentations to their business model. After exhausting these gross emission reduction options, the company will be left with residual emissions along its value chain, or emissions it cannot physically reduce.

From a 2015 base year, if we assume the 10 largest Brazilian companies with net zero goals reduce their gross emissions by 1.3% every year (which is a trajectory consistent with keeping global temperatures from rising more than 2C in 2050), they would still have 26MtCO2e of residual emissions in 2030 and 93MtCO2e in 2050.

These residual emissions are a company’s ‘fundamental’ offset demand, or emissions that have no viable or affordable way of being reduced and must therefore be offset. Less ambitious gross emission reduction pathways – a realistic outcome for oil majors like Petrobras – would lead to even higher residual emissions. Countries all around the world face similar challenges to reach net zero.

Supply

Carbon offset supply reached a record 240MtCO2e in 2023 but still has significant room for growth. Across the four largest carbon offset registries – Verra, Gold Standard, American Carbon Registry and Climate Action Reserve – registered projects have the listed capacity to deliver 1.85GtCO2e of credits annually. BNEF estimates that supply could grow to 4.4GtCO2e in 2030 and an impressive 7.7GtCO2e in 2050. There is no shortage of developers and governments that will create carbon offset projects with the proper demand signal.

Some 87% of this estimated supply in 2030 will come from nature-based solutions, including avoided deforestation (REDD+), reforestation and agriculture. This could drop slightly to 78% in 2050 as technology-based removals, including direct air capture, become more prominent.

Sectors that avoid emissions, including REDD+, clean energy and clean cook stoves, will provide essential ‘transition’ credits, as aforementioned technology-based removal is scaled in size and costs are brought down. BNEF estimates that 85% of potential abatement from REDD+ can be reached by 2030 with proper investment. This makes the coming years essential for large, nature-heavy markets like Brazil.

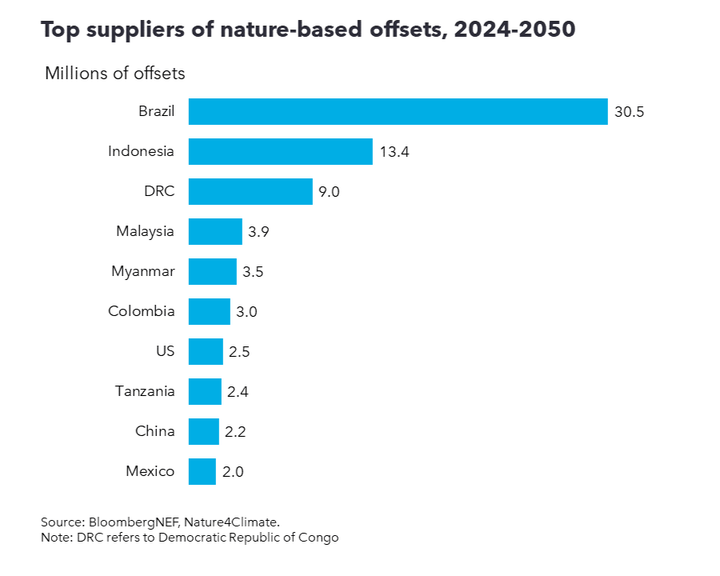

No country comes close to Brazil in terms of nature-based abatement potential. Now the country needs establish itself as a carbon offset supply hub for domestic and international companies with net-zero goals. BNEF estimates that over 2024-2050, the country could collectively create up to 30.5 gigatons of CO2 equivalent of nature-based carbon offsets. With proper investment, some 75% of the abatement in Brazil to 2050 could come from avoided deforestation, known as REDD+, followed by reforestation at 23% and sustainable agriculture practices at 2%.

Brazil’s fledgling offset market will need to make a big U-turn to reach this potential. The country issued a record 25.4MtCO2e of offsets in 2021, but supply plummeted to 7.6MtCO2e in 2022 and 5.6MtCO2e in 2023. Issuance has historically been top-heavy, coming from a handful of large REDD+ projects with inconsistent quality.

The development of domestic regulations and methodologies for carbon offset projects, alongside drawing inspiration from successful big projects deemed ‘high quality’, should ensure that Brazil sustainably scales up its carbon offset supply. However, guidance from groups like the Integrity Council on Voluntary Carbon Markets will also help ensure future supply is compliant with global standards.

Pricing

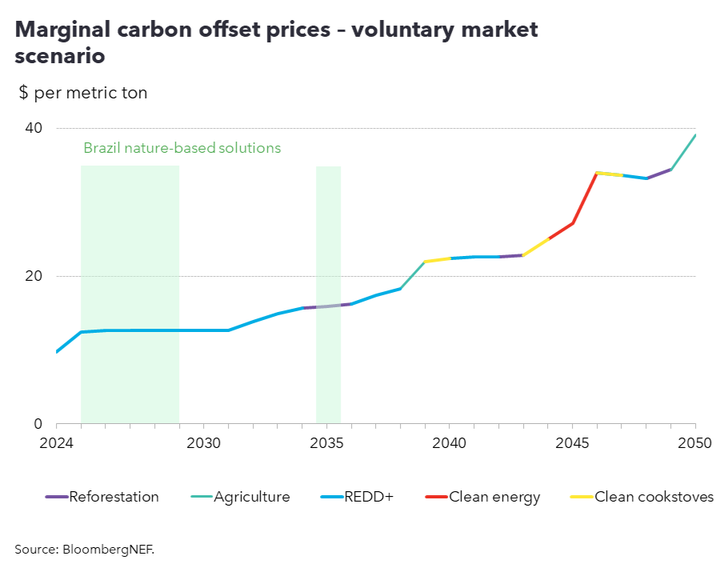

Under the current structure of the voluntary carbon market, where supply is traded globally between different countries, Brazil is poised to set global prices for carbon credits in future years, should it make the necessary investments into building up an inventory of projects. Assuming the voluntary carbon market retains its current structure out to 2050, BNEF estimates the marginal price of carbon credits from 2025 to 2030 could be set by Brazilian REDD+ projects at $13 per metric ton. Brazilian projects once again set global marginal prices in 2035 – this time from reforestation projects at $16 per ton.

The dominance of Brazilian nature-based solutions means that any changes to cost, supply or demand in the country could have ramifications on global demand and prices for credits. This is not dissimilar from OPEC’s role in influencing global oil markets.

Stay up to date

Sign up to be alerted when there are new Carbon Knowledge Hub releases.