Public acceptance of carbon pricing

intermediate

|

26 Sep 2024

Public acceptance of carbon pricing

Public resistance has hampered efforts to scale up carbon pricing around the world. Opposition from local populations has led governments to end plans to implement a carbon price or tax (as seen in the US, for example), drop efforts to make such a policy more ambitious (such as France), or scrap an existing carbon pricing program (such as Australia). Governments have to balance the need to introduce an effective carbon tax or market, which by its nature will require some change in the status quo, and the need to avoid unworkable public opposition.

Key message

Governments planning to introduce a carbon tax or market need to take steps to bolster public acceptance. Important factors are measures to ensure fairness,

the policy name, and how revenue will be spent.

Perceived fairness

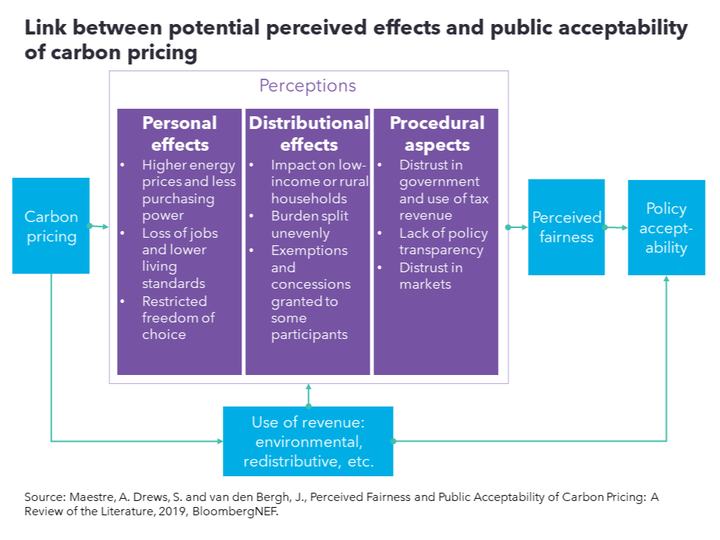

A significant factor in determining whether the public views a carbon price in a positive light is its perceived fairness. Such concerns can take a range of forms and may relate to the impact on the individual in question (personal effects) – for example, whether it will increase energy prices or lead to job losses. Alternatively, they may be associated with the effect on others (distributional effects), such as the impact of the policy on low-income households.

In addition, the public may be concerned about the overall design of the carbon price, policy transparency, use of stakeholder consultation, and the implementation of the carbon price (procedural aspects). The public’s willingness to pay a carbon price is a function of political and cultural views on the need to cut emissions and may correspond to traditional political divisions between the left and the right.

In terms of distributional effects, carbon taxes and markets can be regressive. If a carbon price is applied uniformly across the population, low-income consumers pay a disproportionately higher share of their income on such policies. This is a particular concern where no cost-effective alternative is easily accessible for the technology or process subject to the carbon price, as might be the case if the levy is applied to domestic fuel. There is some evidence that carbon pricing is more likely to be regressive in higher-income countries.

Acceptance may also be affected by the public’s overall trust in the government. Countries with higher trust levels tend to have higher carbon prices. This is especially the case for taxes, where the government has fixed the price, compared with markets. The presence of strong institutions to administer and monitor complex policies may also help.

Potential solutions

Governments have a range of ways to mitigate public opposition. They could seek to lessen any potential regressive effect by making the carbon price paid per unit of emissions proportional to income or consumption. They can ensure that the public has access to a cost-effective, low-carbon alternatives – for example, by subsidizing heat pumps or biomass boilers if the carbon price applies to domestic heating fuel. Alternatively, policymakers can cut other taxes, such as consumption tax on basic products.

More broadly, policymakers can introduce other incentives to promote emissions reduction, thereby reducing the overall tax liability. For example, the Austrian government sought to help blunt the impact of the national carbon tax, which began in July 2022, by introducing subsidies on electric vehicles and low-carbon heating systems.

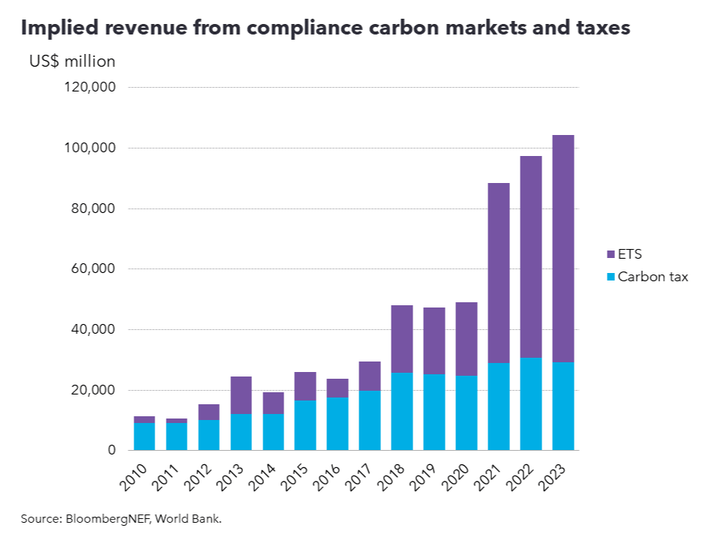

Alternatively, governments can set aside or “recycle” at least some of the revenue from tax collection or permit auctions for specific areas, rather than allocating it to the general budget. This potential is substantial – carbon taxes, alone, in 2021 had implied global revenue of $116 million. Some governments target environmental initiatives – for example, monies raised by permit auctions in California and Quebec are spent on green projects. Others target potential regressive effects – some revenue from British Columbia’s carbon tax funds a tax credit for low-income local residents to help offset the levy’s impact.

There is some evidence that people prefer revenue to be used for environmental initiatives, rather than to reduce regressive effects. In practice, most programs allocate revenue to multiple areas, including to companies at risk of carbon leakage. In terms of recycling format, uniform lump-sum payments to citizens – as implemented in Switzerland – lead to a larger increase in acceptability than tax breaks.

The name of a carbon-pricing policy is also important. Research suggests that environmental taxes are less popular than subsidies and regulation. It was no coincidence that opponents of Australia’s short-lived Carbon Pricing Mechanism portrayed it as a “tax”, even though strictly speaking it was a cap-and-trade system with a fixed price in the first three years. Communications should use technical and economic language sparingly, as well as references to “costs” and “prices”.

Messaging should instead focus on how the carbon price benefits the local public’s values. For example, in Canada, the federal government has emphasized the link between the carbon price and shared values such as being a resource-based economy and resilient people. In Chile, communications have centered on the broader transition to a low-carbon economy, rather than the carbon tax itself. In Sweden, reforms to the carbon tax have been adopted as part of broader fiscal reforms and conveyed as a package.

Stay up to date

Sign up to be alerted when there are new Carbon Knowledge Hub releases.