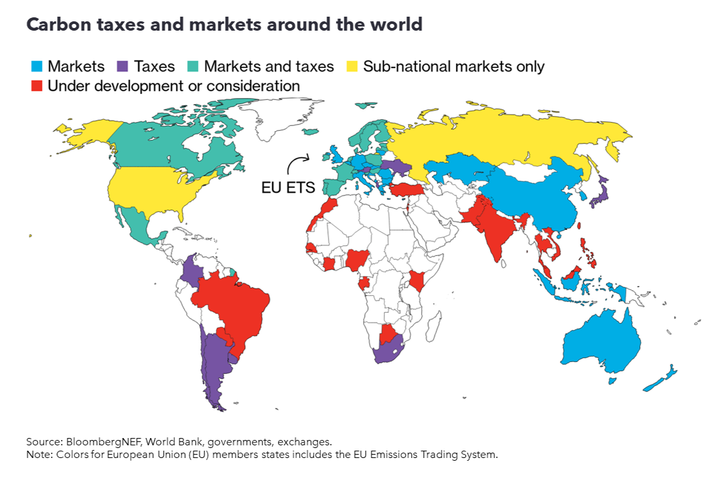

Countries are under increasing pressure to increase the ambition of their short-term climate plans, in time for COP30 Brazil in 2025. In the longer term, governments responsible for more than 90% of global greenhouse-gas emissions have pledged to reach net zero by mid-century, or are actively discussing such a target. As a result, more jurisdictions are introducing a carbon price, as an effective way to drive decarbonization and achieve their green pledges.

At the same time, companies are voluntarily making their own climate plans, and are increasingly required to do so via regulations. While their immediate priority should be addressing their own emissions, some also intend to use the voluntary carbon markets to deliver on their commitments, as do some governments. Broadly speaking, the aim of a compliance carbon price is to make polluters pay for each unit of emissions, typically through a tax or market-based system.

Key message

Carbon pricing can be an effective policy tool to make polluters pay for their greenhouse-gas emissions. Out of the 60 or so programs around the world, the most common types of compliance program are taxes and emissions-trading programs. Broadly speaking, the former guarantees the carbon price, and the latter delivers a guaranteed reduction in emissions. In addition, the voluntary carbon markets enable companies, consumers, and governments to offset their emissions by purchasing and retiring offsets.

Markets

The most common type of compliance carbon market is a ‘cap-and-trade’ scheme such as the EU Emission Trading System, and a baseline-and-credit scheme such as Australia's Safeguard Mechanism. A cap-and-trade scheme generally works as follows:

-

The government or regulator sets an upper limit or cap on the greenhouse-gas emissions covered by the program.

-

It then distributes tradeable certificates up to the cap. These permits represent the right to emit a fixed amount of greenhouse gases – typically 1 metric ton of CO2-equivalent.

-

The government may also provide some permits for free, especially to sectors facing competition from companies overseas (due to the risk of carbon leakage).

-

At the end of the compliance period, a participant must submit enough permits to cover its emissions.

-

If it does not have enough permits, it has various options depending on how that scheme is designed. It can buy more permits from other scheme participants with a surplus, from the secondary market, or from the government itself. It can buy offsets from projects to reduce, remove or avoid emissions. Alternatively, it can reduce its own emissions, or pay a fine, which is typically much higher than the CO2 price.

An alternative type of market-based program is a baseline-and-credit scheme, which has no upper limit on emissions. The government sets a baseline for each participant based on absolute emissions or emissions intensity. Participants earn credits for emissions below their baseline and must buy credits if they exceed their target.

Through the voluntary carbon markets, companies, governments, and consumers choose to offset their emissions by buying and retiring carbon credits. These units are produced by projects that reduce or remove greenhouse-gas emissions and can be traded with other market players.

Taxes

Argentina, Sweden, and South Africa, for example, have opted for a carbon tax, which requires companies and individuals to pay a fixed price per unit of emissions. It may be applied to the supply, retail, import or use of fossil fuels, and the tax rate may vary by fuel or sector. In addition, some policies allow the use of carbon offsets from projects to reduce, remove or avoid emissions.

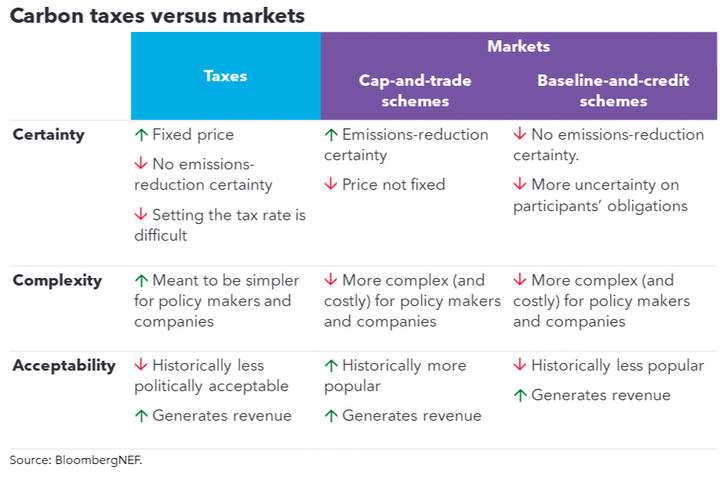

Mechanism choice

For policymakers, the choice between a carbon tax and market is mainly a choice between a guaranteed price and a certain change in emissions. A tax does not guarantee a particular decrease in emissions, but it provides certainty about price per unit of emissions. This is crucial to ensure that a carbon price will alter behavior and enables the taxpayers to plan investment. However, setting the tax rate is difficult. If it is too low, companies and households will continue polluting and just pay the tax. If too high, costs could rise higher than necessary to reduce emissions.

An emission-trading scheme (with an absolute cap) is guaranteed to achieve a certain emission reduction and can send a clear long-term signal to investors. But the price is set by market forces, meaning uncertainty for scheme participants. Historically, they have also meant to be more politically palatable than carbon taxes. One reason may be the concessions offered to certain participants, particularly those exposed to global competition. Cap-and-trade schemes generally offer more flexibility in terms of compliance for participants compared with taxes. But they also tend to be more complex (and costly) from an administration and compliance perspective. Both taxes and markets may be used to raise revenue, for example through auctions of permits. These funds may be used to increase public acceptability.

Baseline-and-credit schemes are meant to make it less likely than emissions-trading programs that participants simply pass on the cost of compliance and is meant to better protect companies exposed to international competition. Unlike cap-and-trade schemes, emissions targets are moveable as they are based on emissions per unit of production (emission intensity). If a goal were missed in one year, the regulator could reset baselines in future years, creating uncertainty for participants. Another downside is that the baseline is determined in advance, but the actual volume of production and its emission intensity is not known until the end of the period.

Stay up to date

Sign up to be alerted when there are new Carbon Knowledge Hub releases.