Governments are increasingly concerned about the risk of carbon leakage, whereby companies shift operations abroad to circumvent obligations imposed by a domestic compliance carbon market or tax, as well as other environmental policies. As a result, carbon border tariffs are climbing the political agenda as a way to implement more ambitious climate regulations without hurting the competitiveness of domestic companies against imports and to guard against carbon leakage. This type of policy also enables jurisdictions to tackle their supply-chain emissions, which can be considerable for economies dependent on imports of carbon-intensive materials and products.

A carbon border tariff assigns a price to the greenhouse gas emissions from the production of imported goods. It is meant to level the playing field for domestic producers. Consequently, export-reliant economies, especially those focused on the manufacture of emissions-heavy goods, would be more exposed to the effects of a carbon border tariff.

Key message

Carbon border tariffs assign a price to the emissions of imported goods generated by their production processes. These policies are becoming more popular among governments looking to impose tougher environmental regulations without damaging the international competitiveness of local companies and leading to carbon leakage. The European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, known as CBAM, was the world’s first carbon border tariff to be implemented at scale, but more governments have kicked off discussions about a similar measure.

How a carbon border tariff works

A carbon border tariff’s main objective is to ensure that domestically produced goods face the same cost of carbon as their international counterparts. It does so by imposing a top-up on the carbon price paid by importers to match to either the local carbon tax or cost of emission allowances.

The precise design of a carbon border tariff may vary across jurisdictions but there are some commonalities across schemes such as the EU and UK’s incoming CBAMs. Their basic steps are as follows: importers of goods subject to a CBAM disclose the volume of emissions embedded in their products. This disclosed quantity is verified by an independent body and importers obtain and surrender an equivalent number of certificates. Each certificate represents one metric ton of CO2 equivalent. If an explicit carbon price has already been paid in the country of production, an equivalent amount could be deducted from the total number of certificates that importers would otherwise have to surrender.

EU's CBAM is a world first

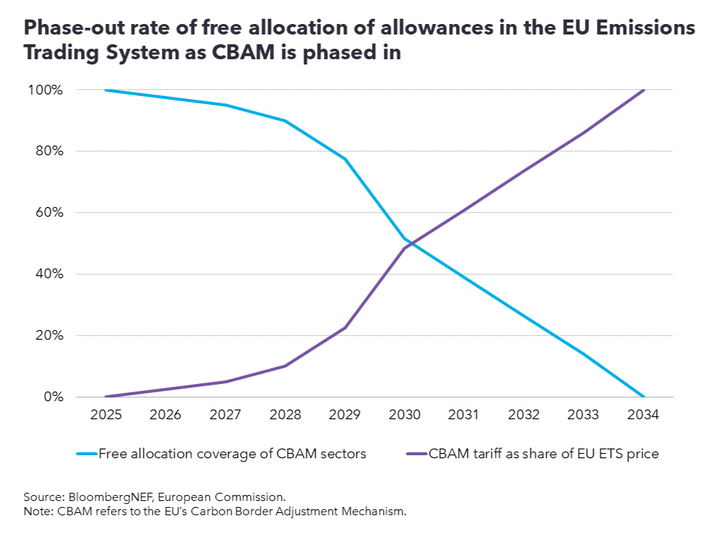

The EU launched the world’s first carbon border tariff in 2023 with a three-year transition period. The current setup of the bloc’s compliance carbon market – known as the EU Emissions Trading System – means heavy industries receive a substantial number of allowances for free to cover their emissions. This is designed to prevent carbon leakage. But as the EU’s CBAM is phased in, the volume of free emission permits handed out to industrials will be phased out, which should spur them to decarbonize.

The EU’s CBAM will initially cover cement, iron and steel, aluminum, fertilizers, electricity, and hydrogen. During the transition phase from 2023 through 2025, importers from these sectors are only required to disclose the emissions embedded in their imported products. This includes direct emissions – those released during the production of imports – for all identified sectors, and indirect emissions from the generation of electricity consumed by some industries like cement and fertilizers. The biggest exporters of these goods to the EU include China, India, Russia, Turkey and the UK.

From 2026, importers will need to buy and surrender certificates covering the associated emissions of their products. The price of the certificates will be derived from the weekly average auction price of EU ETS allowances. The fee could be at least partially waived if a carbon levy has already been paid in the country where the goods were produced.

Moving forward, the EU aims to extend the carbon border tariff to all sectors covered by the region’s carbon market. The bloc’s reliance on imported goods means the CBAM would cover more than half the emissions included in the EU ETS.

Capitalizing on opportunities

A carbon border tariff like the EU’s CBAM could disrupt existing trade flows by channeling demand away from economies with dirtier production processes to those with cleaner manufacturing footprints. This could potentially create opportunities for exporting markets with less emissions-intensive industries.

It could also spur governments to introduce more low-carbon policy support to drive domestic decarbonization. For example, China plans to add steel, aluminum and cement to the list of polluting sectors covered by the national emissions trading system. By introducing extra costs for emitting carbon, the Chinese government hopes that potentially lower emissions from these industries will cushion the impact of the EU’s CBAM.

Realistically, the actual impact of the EU’s CBAM on decarbonization is limited for some industries and countries. In the case of China’s steel industry, the effects of the levy will be minimal despite a 49% increase in delivery costs projected by BloombergNEF, because the nation exports less than 1% of the steel it produces to the EU.

A carbon import tariff may also incentivize jurisdictions to introduce new carbon-pricing mechanisms to circumvent or weaken the impact on their industries. For example, Turkey’s Green Deal Action Plan, published in 2021, stated that the decision on whether to introduce a domestic carbon price would depend on the introduction of the EU’s CBAM. In 2023, the Turkish government and European Bank for Reconstruction and Development published a report exploring the implications of a domestic carbon price on the economy’s exposure to the EU’s CBAM.

Although safeguarding exports from the effects of CBAM is a common objective for governments, the collective push for more ambitious carbon policies will encourage cleaner industrial production in exporting countries and strengthen global decarbonization efforts.

The EU’s CBAM has also appeared to spur other jurisdictions to think about creating their own equivalent carbon border tariffs. The UK has made the most progress, with the government announcing in 2023 a CBAM would be implemented by 2027. In the US, the idea of a CBAM is gaining momentum since several related bills were introduced in 2023. These include the Clean Competition Act, the Foreign Pollution Fee Act, and the PROVE IT Act. While they have not been legislated, there is strong bipartisan support for these proposals.

Besides the UK and US, Australia and Canada are also exploring the establishment of their own carbon border tariffs through consultations with international trading partners, although little progress has been made since the discussions began.

Another opportunity created by a carbon import tariff is the revenue generated, which could be used to support social welfare and other low-carbon initiatives. In the case of the EU’s CBAM, the European Commission estimated in 2023 that the mechanism could generate €1.5 billion (in 2018 prices) annually as of 2028. However, this revenue recycling practice has been embroiled in controversy as critics believe the funds should be channeled to emerging economies, to help decarbonize their heavy industries that are affected by the EU’s CBAM.

Challenges of carbon border tariff implementation

In the case of the EU’s CBAM, several essential elements needed for greater clarity remain unconfirmed. These include the phase-out of free allocation for covered sectors, crediting carbon pricing in countries or origin, and the date from which electricity-related emissions will be included.

Exporting countries may view carbon border tariffs as a protectionist trade measure, as evidenced by the reaction of some to the EU’s CBAM. In May 2024, the then trade minister for South Africa, Ebrahim Patel, said the country was considering lodging a formal complaint about the EU’s CBAM with the World Trade Organization.

Other than addressing trading partners’ concerns about protectionism, entities included under the EU’s CBAM need to ensure their direct and indirect emissions are disclosed accurately and in a timely manner to avoid being penalized. If companies do not submit a report of embedded emissions in imports or do not address the errors highlighted by the respective authorities, they could face penalties of €10-50 per metric ton of unreported emissions. Faced with the task of emissions accounting, companies could be ill-equipped to comply with the relevant regulations.

Although one of the main objectives of a carbon border tariff is to ensure carbon pricing does not limit local companies’ ability to compete with cheaper imports, these firms could end up facing higher material costs. This could be a particular pressure in the near term as businesses struggle with the development and deployment of the expensive low-carbon technologies needed to decarbonize their operations. Unless tax revenues from CBAM are channeled to support domestic industries in making these decarbonization investments, the mechanism will do little to help struggling companies.

Stay up to date

Sign up to be alerted when there are new Carbon Knowledge Hub releases.